Writing dispatches under battlefield conditions.

With the coming of Remembrance Day we thought we would publish a short note on some preliminary work we undertook on some of the Great War diaries of the Princess Patricia Canadian Light Infantry.

We looked at the messages being passed between the officers in charge of various companies as they battled at the front and the commanders some distance behind the lines. In total there are about 200 dispatches extracted from the war diary from about a dozen officers. We wanted to know: When crises intensify at the Front, do the officers in charge write less or not at all until the fighting slows? We speculated that this would be the case owing to the confusion and the increased need for hands-on leadership at such times.

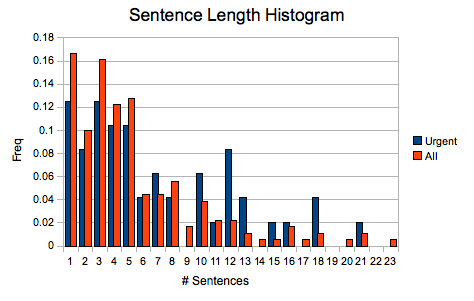

We found that on the contrary, at the times of greatest activity, messages from the officers in charge at the front not only increased in number but in length at the times of greatest activity, when the troops and their officers were under fire or in other critical situations. These urgent messages tend to be an average of two sentences longer than other non-urgent messages.

The histogram shown here gives an idea of what is going on: messages get longer the more adverse front line conditions become. Using close reading techniques, we analyzed the long messages that our data-mining search had identified and drew the following conclusions about why these were written at the very times that we would have thought officers were far too busy to write them:

Front-line officers could not always follow the orders issued by commanders who were frequently working without up-to-date information about the situation on the ground. When HQ commands were not carried out at the Front, the officer in charge would write out a fuller explanation of his company’s actions than he would ordinarily make so as to explain decisions made by junior officers at the front. These officers must ask for permission after the fact: “I trust this meets with your approval.”

Furthermore, since the commanders lack crucial information, officers-in-charge need to convey that information thoroughly and accurately, which explains the details and time taken by company officers to write comprehensive dispatches to their superiors.

These longer memorandum also offer evidence of group decision making when confusion at the front is particularly acute: front line officers will make contact with other officers in charge of adjacent companies in order to establish a clearer picture of what is occurring at the front and to form a plan that they then forward back to their commanders: “I talked the matter over with Major Hudson of the RCR and he and his junior officers agreed with me that the trench was too crowded and that I should withdraw.”

The data used in this specific research is derived from the war diaries transcribed by volunteers at the Canadian Expeditionary Force Study Group and the analysis is an ongoing collaboration between Shelley Hulan and Rob Warren.

- Log in to post comments